By Elesha George

Ruleo Camacho, a Marine Ecologist at the National Parks Authority (NPA), is assisting in a regional effort to understand why long-spined sea urchins have been dying.

He is extracting tissue samples from the species to understand and to identify the pathogen that has begun to wipe out the creatures across the Caribbean.

Camacho, whose primary responsibility is management of the marine area at the Nelson’s Dockyard National Park, is working with other researchers across the region. The samples they collect will be sent to Cornell University in New York for testing.

The long-spined sea urchin – or diadema antillarum – is considered one of the most important marine herbivores in the Caribbean. It primarily consumes algae, and maintains open spaces for corals to grow. Along with the doctor and parrot fish, it helps maintain reef health that results in the turquoise beaches that we see here in Antigua and Barbuda.

The sea urchin die-off was first identified within the national park around Falmouth Harbour in March.

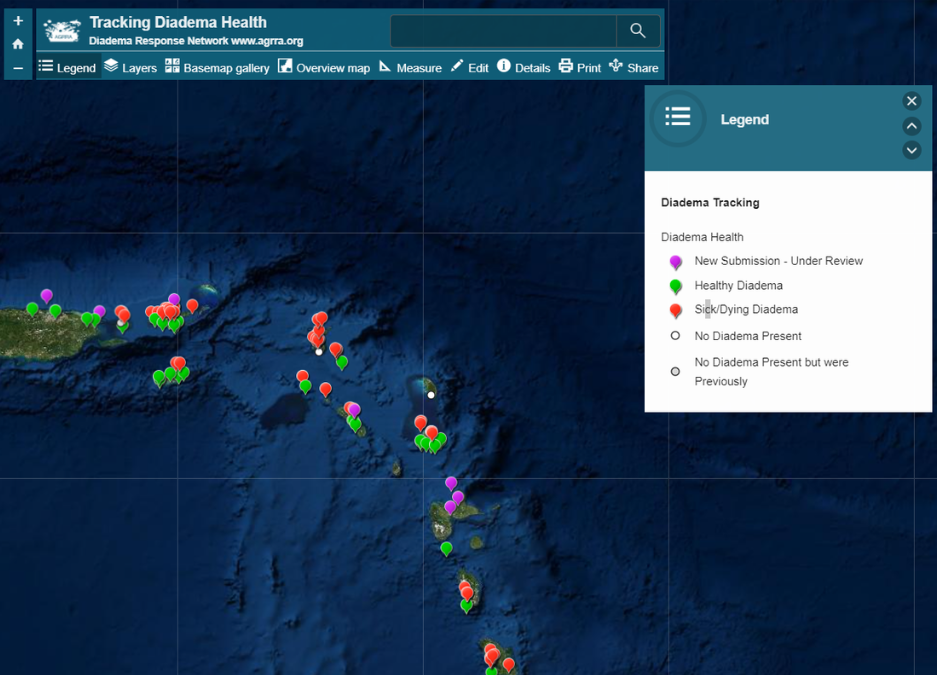

The Authority began to receive additional reports of urchins washing ashore at English Harbour, Pensioner’s Beach, Deep Bay, and on the north side of the island, within a week of them putting out a public call to help identify the locations of sick urchins.

According to the ecologist, “There’s been this formation of a diadema response network that’s trying to better understand how it’s spreading, how fast it’s spreading, and possibly what can we do about it.”

Researchers in Antigua and Barbuda began that exercise this week, and they hope to continue into next week.

“We’re essentially taking tissue samples, preserving them, and then they’re being sent to Cornell University for some genetic analysis because what we’re trying to do this time is see if we can identify exactly what’s causing it,” Camacho said.

“And, if we know what’s causing it, we might be able to better figure out how to mitigate it.”

This time around, he said, the disease seems to be “spreading faster” than a previous epidemic in 1983.

“The progression between a healthy and sick sea urchin takes about two to five days … it’s happening very fast,” he explained.

The disease may be water-borne, and there are suspicions that the unknown causative agent could be originating from areas with harbours.

“It tends to be starting from harbours,” Camacho remarked, “where there’s more boat and yacht traffic. So, it may be travelling on those vectors and getting into other areas.”

Before the 1983 epidemic, Camacho recalls that urchin densities were about 10 per square metre on average. He said this helped to clean and maintain the health of coral reefs.

“So, if you went one step forward … and made a box there are about 10 urchins in that box – that’s what it was before. Now, you’d have to do that 10 times to find one urchin. That’s how low the densities became,” he said.

Sampling and communication between Caribbean countries back then was inadequate to determine the causative agent. Eventually, mass death stopped on its own and allowed the sea urchin population to regenerate.

“It started to pop up in areas like Jamaica and then it rapidly spread, and within a two-year period over 90 percent of the urchins within this region died off,” Camacho added.

In mid-February, authorities in Charlotte Amalie Harbour, St Thomas, however noticed a phenomenon that was very similar to what started 39 years ago in Jamaica.