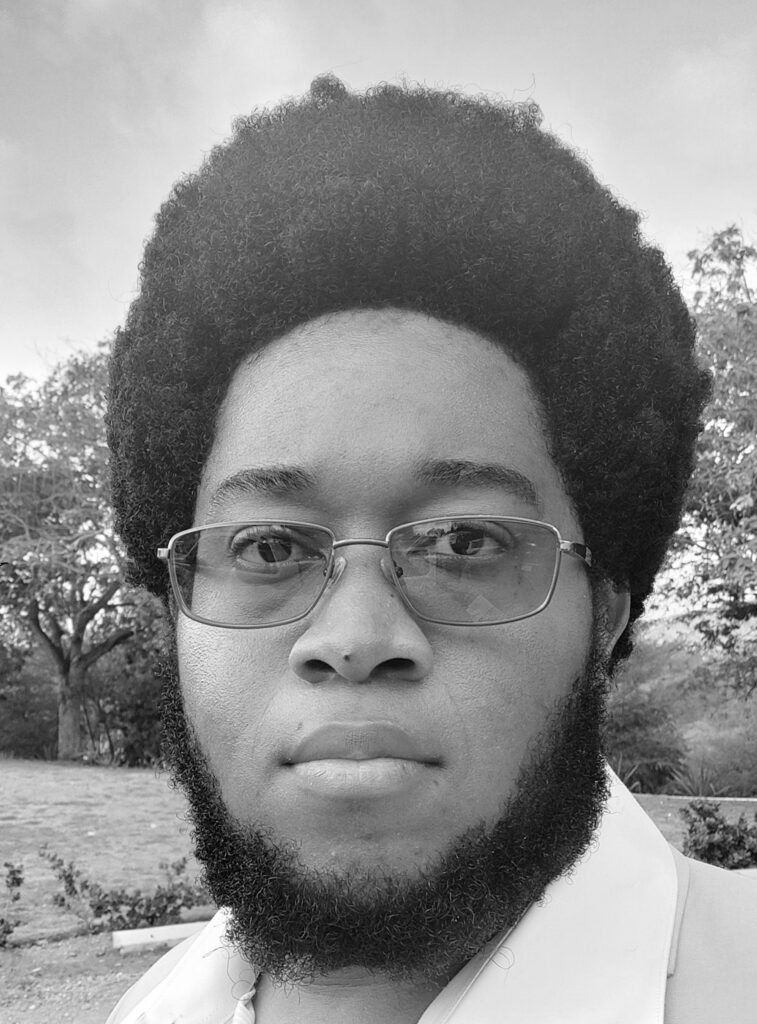

By Kieron Murdoch

“You look [N-word]-ish” is how someone once described my appearance some years ago when I was at the age where I was still in secondary school. As deeply offensive as the statement was, as usual it was rolling off the tongue of another Black person. By this time, I had become rather accustomed to the incessant nagging of friends and strangers on the appearance of my hair, which was then and still is plainly an afro.

I resolved to ignore them since taking the time to explain to each why their incessant nagging was a reflection of their learnt and unacknowledged prejudice toward Black features became an exhausting exercise. Interestingly, I have found that as an adult, far fewer persons are likely to offer unsolicited comments about the appearance of my hair. But in earlier years it was very much a norm.

Even in State College there was one lecturer who would offer soft hints and advice to the effect of telling me that I ought to tame the woolly monstrosity protruding from my head. Then there was that policeman on way to State College who could not restrain himself from calling out “Dwight Venner!” whenever he observed me going about.

It was through interactions of this sort that I eventually developed some degree of numbness to the issue of negative attitudes toward Black hair. It no longer stirred me. I had discussed the issue so many times, so often, with so many people in an effort to raise their awareness of the issue that I simply could not be bothered anymore. To warn off potential challengers, I would wear an expression that equated to the statement, “don’t speak to me”.

But nonetheless, I had found that over the years, that we as a people – of all colours and textures – were having the conversation about our often negative attitude toward natural Black hair more and more. As time moved on, more and more people demonstrated a willingness to acknowledge the existence of that prejudice and the need to resist it.

Recently however, I have been dismayed by a particular incident that has demonstrated that many in our society still appear to have some difficulty in identifying this issue for what it is – prejudice toward natural Black hair. That prejudice includes as distaste for the various traditional and modern ways in which Black natural hair is neatly, cleanly, and attractively styled.

You know the incident of which I speak. A five-year-old schoolgirl meant to attend a Seventh Day Adventist school here in Antigua and Barbuda became the spark for an inferno of commentary and debate over school rules, religious freedom, and prejudice toward Black hair.

I was heartened to see the government took note of the incident, and resolved to create a broad policy toward hair grooming in all schools. The policy appears aimed at creating a uniform standard which avoids penalising students for the texture, length or style of their hair, while still requiring that it be neat, clean and tidy. Common sense prevails, yes?

Although, state officials, members of the public, and most recently the President of the South Leeward Conference of Seventh Day Adventists, Dr Carson Greene, have rather unfortunately mischaracterised this dispute as one surrounding religious freedom.

This is because the school and the church seem to have taken the stance that their rule against locs is part of their religious observance, whilst it has been suggested, though never explicitly reported, that the schoolgirl turned away due to her locs was of the Rastafari faith, or perhaps her family was. Rastafarians grow their hair as part of their religious observance. So for some, this conflict appears to have been a clash of faiths.

Additionally, the statement from government spokesman Lionel Hurst after last week’s Cabinet meeting suggested that there may have been other anecdotal reports considered at the ministerial level of Rastafarians particularly encountering problems at other schools because of their hair. This was not clearly stated, so it might not be the case.

But truthfully, whether or not the girl or her parents are Rastafarians, and whether or not the school was an Adventist school is entirely not the point. At the root of the issue is prejudicial attitudes toward natural Black hair and the norms of styling it.

Locs are not exclusive to Rastafarians. Non-Rastafarians have locs. It’s a fashionable style for some, as much as it is a faith-based practice for others. And rules banning locs are not exclusive to the Seventh Day Adventist school in question. Such rules have been found in public and private schools, both religious and non-religious, as well as in workplaces across the country.

I say this to say, that the school in question and girl in question are together but a single example in a much broader social space where systematic prejudice toward Black natural hair is a lessening problem, though still a serious one.

It can at times be very difficult to call ourselves out for our own prejudices, particularly when they are things we have learnt unknowingly and practice unknowingly. Why have you never shown your hair? Why do you cut it down to the scalp all the time? Why do you perm it over and over? Why do you cover your head with false hair? Why do you prefer partners with lighter skin? Why do you think you are somehow less because your tone is dark? Why do you just hate to see locs on a person’s head? Why does it upset you so?

Answering those questions can be unsettling for an individual, so we often shy away from answering truthfully. But we ought to answer truthfully. It is the only way of recognising the subtle ingrained values each of us has picked up from living in a society so heavily affected by its highly racist and ferociously classist past. But again, acknowledging one’s own prejudices is a difficult thing to do.

Ask a Black West Indian if they are racist, and they will immediately tell you “no”. In spite of that, you may hear them bully a friend calling them “Black and ugly”, a highly offensive phrase Black people often use toward each other.

You see, the type of prejudice we display toward each other in the stances we take and rules we make are less often part of a conscious, aggressive or superior attitude. Rather, it is so often subtle – values we unknowingly adopt overtime which betray a subconscious view that we have toward a particular group of people – in this case, ourselves.

The plantation society of the colonial era was one in which our Black ancestors learned to be racist toward themselves – to believe genuinely in the inferiority of their shape, tones, textures, intelligence and ability. We have thereby been bequeathed a loathsome obsession with the tone of our skin, the curly texture of our hair, and the shapes of our faces.

We treat these things as incorrect, unfortunate handicaps, or things in need of improvement or correction. It is an abhorrent notion that must be recognised and resisted wherever it manifests itself in the modern world.

We are also a highly multiracial people. We have different racial groups and so many of us are of a multiracial background. So many of us who are of Black African descent in the West Indies today also have European, Middle Eastern, Amerindian or East Indian ancestry. Sometimes, it is so negligible that you can’t outwardly notice. At other times, it is pronounced in a person’s features.

Colourism and hair prejudice within Black West Indian communities was at one point an unchallenged norm, with fair skin and “good hair” being the coveted and sought after qualities in oneself and in one’s partners. Today, amongst ourselves, although we have been resisting for many generations that inward, self-deprecating, inherited self-prejudice, it is nonetheless still subtly present in some of our values, our opinions, our perspectives and certainly in our institutions.

Institutions outlive people although people shape institutions. Consequently, you may enter an institution such as a school and find a rule that has been on the books in some way or form for several decades, and comes from a time when our ability to recognise the subtle prejudice that we were meting out against each other was not as great as it is today.

Institutions last for generations, and so do their rules and cultures those rules create. It is therefore necessary that today’s leaders do not simply perpetuate without thought the norms, rules and expectations which their institution have had for decades. Rather, they ought to take a moment to examine them and the extent to which they are reasonable and necessary.

So this begs the question: Why did the rules in that school prohibit locs? That is the very obvious, very basic question that the President of the South Leeward Conference did not answer in his recent press release. His words only sought to balance his church’s freedom to practice its religion as it sees fit, with the religious freedom of Rastafarians.

But let’s assume the child in question was not a Rastafarian, and she simply had locs because they were fashionable. What is the justification for the rule banning locs? You should not need an exemption on religious grounds in order to be allowed to have locs as a style in any school. Nor should you be asked to cover your head, as if your locs were an offensive sight to the school population.

So I ask again, why would any school, or any workplace, or any other institution seek to prevent anyone from having locs? The answer is that some people simply have a negative view of locs. They don’t believe the style is presentable or attractive, nor do they think one looks “well groomed” while sporting them. Why? Why do they feel this way?

What is it about locs that people find so intolerable that they explicitly prohibit them in the rules for their workplaces or the rules for their schools? The same question could be asked of many of ways of keeping one’s natural hair. For simply having an afro, no matter how levelled and how routinely combed through, I was deemed “ungroomed” by many. Many girls who style their natural hair in very simple ways will be told that it is “ungroomed” or that they are having “a bad hair day”.

Again, I argue that we are manifesting the prejudices against Black features which were born in, and handed down from a racist plantation society. This is not a new discussion or a new problem. Black communities from Brazil to the Dominican Republic, to the United States, to South Africa, grapple with the same issues. Black thinkers, activists, orators, poets, and change makers have talked about this issue for more than a century.

The fact that we are still unable in certain scenarios, to appreciate the broader problem of hair prejudice is a little disheartening. Having locs is a normal, fashionable, and acceptable way of styling natural Black hair and has been for long enough that we ought to be at peace with it in 2022. And yet, the rejection felt by that five-year-old girl because of her hair is the same rejection which many have met in other schools, in business meetings, in job interviews, and in the workplace. It really ought to stop.

We must enter a phase of society where the ‘isms’ that characterised the past do not hold such a powerful sway over our behaviour. We must also be able to recognise those attitudes and consciously resist them. Lastly, we must think about the people affected by our attitudes and the stances we take.

There is a five-year-old girl somewhere who has been made to understand that her locs are a cause for her to be rejected. Not her behaviour, not her cleanliness, not her performance. She was rejected at school because of her hair, in Antigua and Barbuda, in 2022. Think about that.