By Nathan Wilson

I could barely contain my excitement as I waited for the go-ahead to board the boat to Great Bird Island.

I was eagerly looking forward to the trip because I had nothing but happy memories of the solitary visit to the island over a decade ago. There was one difference between my first visit and this trip that I was about to embark on, however: whereas my thoughts were strictly on the prospect of having fun before, now I was keenly aware of the possible environmental consequences of my visit to the island.

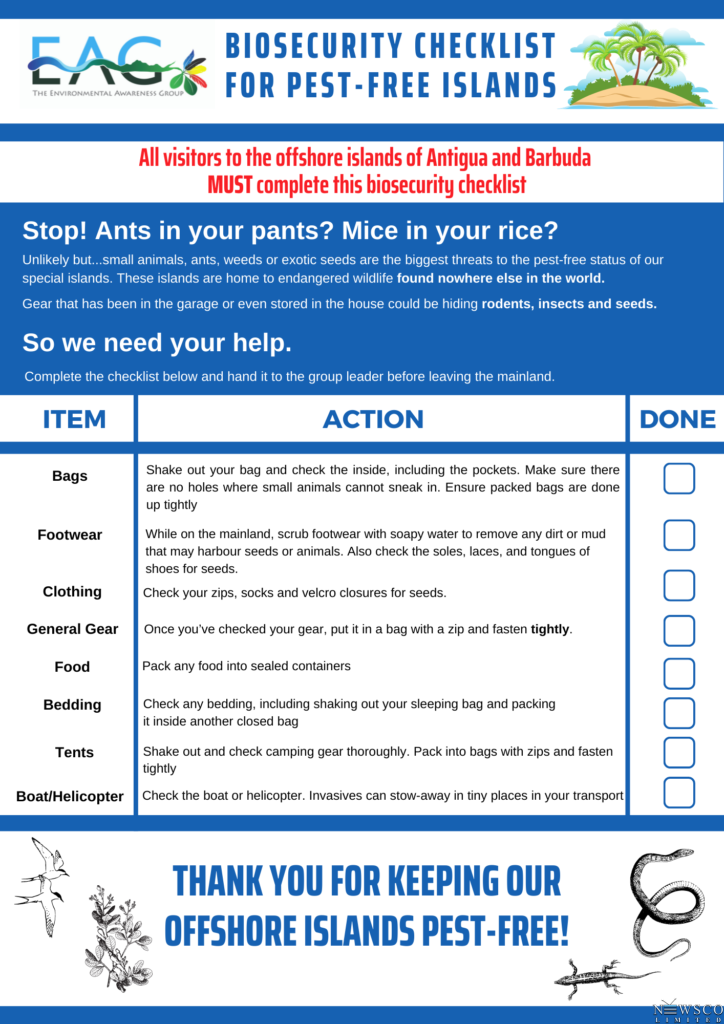

“Stop! Ants in your pants? Mice in your rice?”, a humorous reminder to do my biosecurity checks before we set off. I ran through the checklist, examining my bags and clothes to ensure that there were no small creatures or seeds piggybacking in or on them, and scrubbing my shoes.

This checklist is an important procedure for invasive species monitors and other visitors accompanying the EAG before trips to our offshore islands.

Why? In conservation terms, biosecurity is defined as measures designed to reduce the risk of the spread of invasive alien species and quarantined pests. The word may conjure up images of persons walking around in hazmat suits spraying surfaces with disinfectant, and other things associated with a disease outbreak.

Well, biosecurity is serious, but it can involve less blood pressure-raising activities. No matter how mundane the measures seem to be, it often still is a matter of life and death for animal and plant species.

This was and is very much the case for several species that can be found on the offshore islands in the North East Marine Management Area (NEMMA), and on Redonda.

Back in 1995, a survey of Great Bird Island found that there were only 50 Antiguan racers on the small island. After the clearing of rats off Great Bird Island, the racer population has grown to the point that there are now approximately 1,200 today, on four of our offshore islands.

Redonda also has been cleared of rats and goats, and the results have been breathtaking. Whereas the island looked like the surface of the moon before 2016, it has recovered to become a vegetation-covered landmass that serves as nesting grounds for many species of birds that come there specifically for that purpose, and home to the Redonda ground lizard, Redonda tree lizard, and Redonda pygmy gecko, three lizard species that can be found nowhere else in the world.

Biosecurity is a continuous necessity; several of the offshore islands are visited on a regular basis to ensure that rats haven’t been reintroduced onto the islands during visits, or by swimming from mainland Antigua.

Black rats become reproductively mature at two months and can produce up to 10 young every two months! A single pregnant rat could be the seed that pushes Antigua, Barbuda, and Redonda’s endemic wildlife to extinction within months of their reintroduction to these islands.

In fact, rats and mongooses have been identified as the reason for the disappearance, in the past, of several species from Antigua proper.

On Antigua, we currently have the problem of the giant African snail. Think of how many snails that can be seen crawling around, and it would give you an idea of how serious a matter invasive species can become.

Left uncontrolled, the snails have the potential to denude our islands of their vegetation. We have also experienced the results of other invasives such as the pink hibiscus mealy bug, and the lethal yellowing disease. Biosecurity procedures are important even on mainland Antigua and Barbuda.

While it would be practically impossible to prevent all invasive species from entering the country, we can minimise the likelihood of them gaining footholds on our islands and disrupting the balance of our native ecologies.

The next time you travel between countries, take seriously the Customs forms that you fill out; what may not be a problem in one setting may become a major issue in another environment. We can never be certain what tiny pests might be hitching a ride.